Elpida Karaba

Recommended citation: Karaba, E. (2021). ‘Gendered Aesthetic Techniques and Neo Materialist Prospects. Video-Performance: WordΜord By Vasiliea Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis‘, entanglements, 4(2):66-78.

Abstract

This paper concerns the research of the Centre of New Media and Public Feminist Practices (CNMFPP), based in Greece. The CNMFPP was established at the University of Thessaly, at the Department of Architecture, in 2018, funded by the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (HFRI) and the General Secretariat for Research and Innovation (GSRI) (grant agreement 2284). In particular, it analyses the project of the artist Vasiliea Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis: ‘WordMord’. Her* work addresses urgent feminist issues within the globalised technological condition by activating different aesthetic techniques, such as performative reading, re-enactment, video, and, in its second and third phase, coding and archiving, thus turning our attention to specific situated cases of targeted female* bodies, technology, and the dynamics of articulations and desire as potentia. ‘WordMord’, via different modalities, aims at the circulation of a differentiated meaning, affect, and wording, connecting female, exploited bodies—as diverse as they might be—and encompassing the possibilities of social change and drastic political pathways today.

Keywords:

art, feminism, public space, technology

Introduction

In this paper, we will present the work of The Centre of New Media and Public Feminist Practices (CNMFPP). The CNMFPP was established at the University of Thessaly, at the Department of Architecture, in 2018, funded by the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (HFRI) and the General Secretariat for Research and Innovation (GSRI) (grant agreement 2284). The CNMFPP is a research program, the first of its kind in Greece, which aims to bring forth, both in academic and artistic practice, the issues regarding feminism, technology, the public space and situated politics, in the expanded cultural field. Our tools derive from two different schools of thought: New materialism and Neo-Marxism. Although distinct, they share common ground, offering a complex and challenging epistemological space to address critical feminist issues regarding economy, class, labour, human capital and the so-called cultural industry. At the same time, these tools enable us to comprehend the Anthropocene, the bioethics of biotechnology, and contemporary necropolitics.

VIDEO-PERFORMANCE ‘WORDMORD. Bringing forth the potentia of affirmative ethics

Most particularly, we will present a project which has been developed at the CNMFPP by the artist Vasiliea Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis. Her* work addresses urgent feminist issues within the globalised technological condition by activating different aesthetic techniques, such as performative reading, re-enactment, video, and, in its second phase, archiving, thus further turning our attention to specific situated cases of targeted female* bodies, technology, the dynamics of articulations, and desire as potentia.

According to Rosi Braidotti (2019, p. 155), affirmative ethics concerns ‘a collective practice of constructing social horizons of hope, in response to the flagrant injustices, the perpetuation of old hierarchies and new forms of domination’. Virtuality, heterogeneity, complexities and multiplicities mark a process of becoming, and this desire to expand and enhance our existence is what Braidotti claims to be ‘desire as potentia’ (2019, p. 155).

The artist Vasiliea Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis was invited, in February 2018, to the CNMFPP to coordinate a workshop focusing on gendered approaches to public space in the age of globalised technologies. The focus of the workshop was technology and vulnerable bodies and the workshop emanated from two recent events of extreme public violence, homophobia, and misogyny: the femicide of drag queen and LGTBQIA+ activist Zak Costopoulos, aka Zackie Oh!, in the centre of Athens, and the murder of a young woman, Eleni Topaloudi, at the island of Rhodes—two killings that shattered Greek society. Zak Kostopoulos’ / Zackie Oh!’s inhuman lynching and murder in the centre of Athens, in public view, not only happened in close temporal proximity to the rape and killing of Eleni Topaloudi in Rhodes but is also symptomatic of the vulnerability of specific targeted bodies. The female* body, as well as the body of queer and trans subjects, is perceived as a vulnerable body in the public space, as a body without protective tissue.

The participants in the seminar were invited to search the images and narratives that circulated in mass and social media regarding these two violent events. This primary research was aimed at developing an understanding of the similarities and distinctions between, as well as the hierarchy of, the circulated information regarding the gendered particularities of these two murders. During the seminar, the participants worked with various methodologies. They used image and discourse analysis for deconstructing modes of representation, and they incorporated contemporary feminist theories and multi-modal narratives: oral, textual, sonic and visual. The participants were also encouraged to look at forensic data, in order to turn the attention to the specificities of these cases and the prioritisation of information regarding the two killings. In the case of Zackie Oh!, there has been a more organized, targeted and articulated action on behalf of the LGTBQIA+ community, with collaboration from Forensic Architecture, a multidisciplinary research group based at the University of London. Forensic Architecture has been working with local actors to gather material for the trial of the murderer, and their research has been core in the defense of the victim. Thus, the event of Kostopoulos’ killing became the nodal point for empowering the movement of the LGTBQIA+ community. The case of Topaloudi, on the other hand, has not been such a paradigm shift for the feminist movement and activism. Nevertheless, the two events, though seemingly unrelated, are interwoven in a circle of femicides, and the public discourse and actions around them. Hence, they interconnect in the logic of articulation, of the space which is shaped from the materiality of gathering.

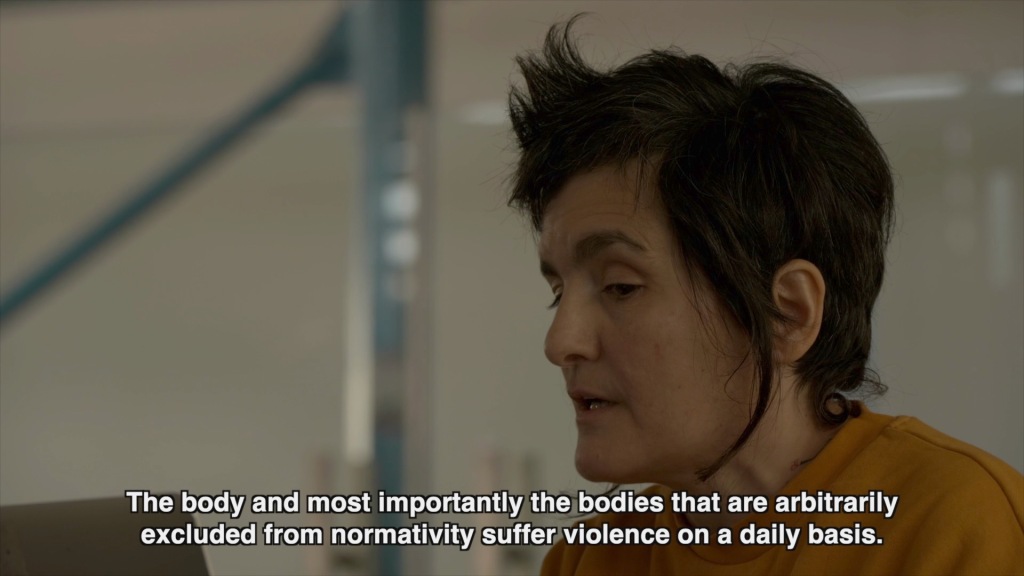

Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis opened the workshop with a performance, a performative participatory reading. Instead of a theoretical, typical academic introduction to the theme of the workshop, Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis invited the students, while they were listening to her* performative thinking, to interact with their cell phones, to touch them with their palms. Some of the participants filmed her*, spontaneously, while s*he was reading. The connection to the device, the videotaping of Vasiliea Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis’ reading, was an unintended re-enactment of the videotaping of Zak Kostopoulos’ murder by some passers-by. Triggering the artistic methods of performance and re-enactment, a work of art was produced at the spot: a short video-performative lecture.

In the performance, the artist articulates her* thoughts—sometimes decisively, sometimes stammering, sometimes rephrasing her* sentences—performing an oral, and at the same time mediated, communication on the relationship between technology, technological devices and the vulnerable body. In her* reading s*he asks: “what is the relationship of vulnerable bodies and new media? If the media are always new, how new do bodies remain? How vulnerable bodies are interconnected via their devices? Which lines of geopolitical routes connect our palms through the slick aluminium surfaces? What alliances of affectful corporeities can we trace? How violence, pain, loss is communicated and processed not via but within new media?”

At the same time, s*he invited her* audience to feel their telephone device and experience, with their body, the mediation of the physical presence of the voice, of the subject uttering the words, of the electronic device and the sensory experience, making all the above an impartible entity. The performative reading, as the artist states, is based on something very straightforward, literal and simple. It concentrates both in the tactility of the (smart) phone device and in the violent reality, which is transformed into data. The video performance is nothing but a statement regarding technology and vulnerability, a bare articulation and voicing of thoughts, feelings and senses, making tangible the mechanics and politics of technological mediation as well as the social perpetration of violence, which they transfer. At that moment, a ‘minor gestural’ work of art was produced and a methodology was tried out, not necessarily purposefully and strategically but organically and procedurally.

In this instance, the device and the fingers are the receptors of different subjects and bodies. The cameras of the participants who filmed the artist during her* reading link with the cameras of the phones that filmed the last moments of Zackie Oh! laying on the street. These different documentation gestures (one from the participants of the workshop and one from the witnesses of the murder) connect, whilst distinguishing different times, spaces and subjects. Similarly, the phone/camera interconnects different types of documentation. It connects, for instance, the people who participated in the seminar with the individuals who witnessed, and cruelly filmed, the event of Zackies Oh!’s murder. The devices / the technological apparatuses / the documentation technologies also connect other spectators: those of the future event in which the video—as a work of art—will be shown.

‘DYSSELECTED’ BODIES and neo materialist prospects

In every instance, touching, filming and sensing the phone connects us, as Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis points out in her reading, to the internal compartments of the phones felt by the small fingers of young Mexican girls who touched these compartments during their manufacturing. An intelligible line, a diagram, is developed where many diverse subjectivities are interconnected. Intelligible lines of geopolitical routes connect our palms with the hard aluminium surfaces of the cell phones, as well as with the exploitation of gendered bodies, a fact that we tend to forget or overlook. Using the phones, different subjectivities are interconnected: the passive witnesses of a murder, the geared participants of a seminar on technology, art and vulnerable bodies, the middle-class visitors of an exhibition, the underpaid female factory workers.

The different subjectivities of these lines are hardly similar, some of them privileged and some of them exploitable. The camera phone and the work of art are traces in a pathway where these distinct subjectivities meet, unexpectedly. And it is exactly in the ontology of these entities—of the phone and the work of art themselves—that these pathways become apparent, connected and making almost tangible the differentiated economies, bodies, and geographies of those different interconnected subjects. It also becomes apparent that technology and access to devices do not necessarily make our world safer, right, or more democratic. The phone and the work of art entail different subjectivities in their use and making; in the production and use of each of them, there are privileged consumers and underprivileged labourers. There are authorised and entitled bodies and expendable bodies related to their making and use. Privileged connoisseurs of art and technology, others less privileged, knowledgeable, trained or engaged meet in a vicious circle of the globalised, technological conditions of cognitive capitalism.

By naming and activating those agents—namely the different subjects as well as the devices—Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis turns our attention, feelings and senses to a trans person in Athens, to female workers in Mexico, and to a student in Rhodes, and invites us to meditate on all of them. S*he also invites us to meditate on the telephone device which long ago stopped being just a tool of communication. It is an agent of biotechnology through which we can think about the various inscriptions upon our bodies, feelings and senses. Think of the many young and teenage girls, such as Topaloudi in Greece, who have to face the violence of non-consensual videotaping of personal, intimate moments, and their sharing on social media (this happened to Topaloudi a few months prior to her rape and killing). These videotaped moments are held as pieces of evidence that, in the event of their rape and killing, are presented as proof and testimony of their promiscuity (as if promiscuity is a crime). Think of the Mexican women who have to fight domestic violence of entitled husbands, the rapes, killings and disappearances that occur when crossing the borders, or the consumption of their female bodies in the manufacturing industries. Think of the constant harassment by the state, the police, or civilians to female and trans bodies. All these bodies of femicides are ‘missing’ bodies, not only because they are killed, raped or have disappeared, but because they have been, already, eliminated, disqualified, or ‘dysselected’ (an idea discussed in an anthology for Sylvia Wynter’s work ‘Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis‘ [McKittrick, 2015]) by those who killed them, those who cleared the evidence of their murders, and those who make hate comments about these women and events on the internet. The telephone device, in this instance, contains and affirms the trajectories linking up gender and socioeconomic issues, as well as strong patriarchal structures in post and tweet culture, as long as sexual determination prevails within capitalist consumer culture, where objects, subjects and lives can be equally desired, devoured, dispensed and consumed.

The produced (video) work, entitled ‘WordMord’, therefore puts us in limbo between subjects and objects, without one being more meaningful and sensible than the other. Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis’ performance invites us to consider further what stands behind the object, thing, or device and how these are thought. For instance, it provokes us to think about what these devices stand for. A feminist orientation to this would be to see anew not only the control and power these devices hold but the vulnerabilities they contain. The connection to the device also makes visible the violence we scopophilically impose on vulnerable bodies in looking at a murder, cases of labor exploitation, or transphobic assault through our devices. Our relationship with our devices is strongly embodied, but our relationship with those vulnerable “other” bodies is, at the same time, multiply mediated and translated to data. This process, according to the artist, entails an inherent violence.

Hence, as Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis refers both to subjects and objects as interconnected, not separate and interchangeable, s*he materially meditates, via the use and the sensory touch of the phone/device, on how the very processes of objectification function. Processes accelerate and condense within algorithmic culture, within the devices we use, and, ultimately, within the devices involved in the murders of Zackie Oh! and Topaloudi. Telephones, selfies, tweets and social media are dominant producers of the subjectivity, desire and objectification of female bodies. Re-enacting a sensorial relation to our devices, by asking the participants to touch, feel, and hold them, brings forth not only the vulnerability but also the invisible desire of the subjects, expressed and circulated via our technological, webbed condition. It brings forth the affective relationships to our objects: the lust and hopes that circulate amongst our fingers and touchscreens, which are transferred, through screens and devices, to the people and things which we love, care for, desire. They are those same desires and hopes that are targeted, by the effort to normalise them, via capitalised and male determined images, algorithms and internet bots, which define our gendered bodies. These are biopolitical technologies that repeat a circle of violence again and again. Readdressing these things in their materiality—obstinately and repetitively, as it happens in the performative reading of the artist—can be a ‘reverse objectification’. It can be a transformative move that connects, articulates and constitutes the subjectivities of ‘dysselected’, ‘missing’ people and the invisible desires that circulate amongst us/them, and towards our devices.

Focusing on the device, the stories it contains, and the diverse and contradictory intentionalities of the thing, we can meditate to unfix the essentialised narratives and images created through media and devices that position certain subjects as vulnerable. As Katharina Wiedlack (2007, p. 249) states, in her essay ‘Gays Vs Russia. Media Representations, vulnerable bodies and the construction of (post)modern’, vulnerability implies dependency, so reducing these subjects to their vulnerability happens for the sake of setting a moral example while vulnerability and dependency create feelings of ‘pity’. The ‘ableist gaze’ reduces individuals to ‘icons of pity’. Let’s, therefore, consider how, at the moment we touch the device, we try to formulate our own connection to it and the stories it tells, through voice or image, about subjects and objects with alternative needs. In order to do so, the artist invites us to focus on the ‘agency’ of the device itself, eradicating its mainstream perception as ‘only a thing’. The device’s involvement in the performance is highly sensory, in the sense that by asking us to feel the device, actually by touching it, sharpens our ideas of what it means to experience via our devices, a phenomenon that happens more and more. In this case, the device is not only an inert, fungible, viable instrument; its status as a mere object is reversed. By eradicating its objectification, by understanding it not merely as an object but as a channel, an agent of desires, feelings, experiences, affect is a process of reversing the very process of objectification. The underlying of this passage, happening in Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis’ performance, from object, to channel, to agent, is an interruption of the process of objectification and vulnerabilisation of certain bodies—by turning them from subjects, to data, to objects—as it happens with female* bodies, targeted bodies through mainstream social media platforms and devices of communication and control.

A PROCESS OF AUTO-POIESIS. GENDERED AESTHETIC TECHNIQUES IN THE EXPANDED FIELD

Subjects and bodies that, in the case of Zackie Oh! and Topaloudi, are female*, trans, raped, murdered, should not be reduced to their vulnerability and mortality; better, subjects should claim their own vulnerability and mortality. Contradictory as this may be, claiming vulnerability by voicing the terms and conditions of vulnerability and mortality is a praxis that challenges the same definition of vulnerability—it claims a differentiation to the dominant power narratives around vulnerable and extinguishable bodies. This could be considered not only as an act of empowerment but as an act of auto-poiesis. According to Braidotti (2012, cited in Dolphijn and der Tuin, 2012), ‘subjectivity is rather a process ontology of auto-poiesis or self-styling, which involves complex and continuous negotiations with dominant norms and values and hence also multiple forms of accountability’. In this case, technological mechanisms should not be conceded only as tools of control. Favouring more granular micro-mapping of the complexities of the material, discursive, and affective entanglements that are situated in online and offline practices of networked intimacy could allow subjects and objects of desire to be circulated. And here we have to reconsider how female* desire is circulated, moralised and criminalised via media and social media, as happened in the case of Topaloudi and her desire, firstly when a private moment of hers was circulated around social media and after her death when this document stood as evidence of her “promiscuity”. And it is exactly why, in order to resist this violent process, that desire should be (re)claimed as power. Desire can be seen as potentia, in Braidotti’s (2019) terms, as mentioned at the beginning of this paper. Thinking and desiring beings keep flowing out of the frames, devices and technologies that attempt to capture them and to foreground complex discursive, material and affective force relations is part of this potentia. We can shatter the representation of murders, bodies, and their perverse documentation, such as in the cases of Zackie Oh! and Topaloudi. All these connections meet in what Braidotti calls, more specifically, ‘ontological desire that orientates, ethically, subjects towards the freedom to express all they are capable of’ (2019, pp. 153-6).

Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis’ reading is an act of expressing, affecting, voicing and ‘messing with’ the audiovisual material circulating in our digital and networked world, with the operation of gendered necropolitics, which ties women’s deaths and extinction to the functioning of modern politics and subjectivities. Vasiliea Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis’ project circulates a different narrative on the two murders; s*he circulates these murders amongst other murders around the world, where the dead meet in the Chthulucene, or, as Haraway (2015, pp. 159-165) would say, s*he circulates them in order ‘to join forces to reconstitute refuges, to make possible partial and robust biological-cultural-political technological recuperation and recomposition, which must include mourning irreversible losses’[1]. Her* video-lecture performance is an ‘audiovisual intrusion’ that politicises both the voices and the silencing regarding these deaths and expendables on which politics are built; this is a performative intrusion into the public as a voice that speaks back and disrupts familiar claims about the political. The naming and the linkage of the possible trajectories between the ‘missing’ people in Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis’ video-lecture performance is a different audiovisual product for the killings of Zackie Oh! and Topaloudi which, by referring to those seemingly unconnected cases, could make us look for possible articulations of different struggles. Topaloudi, Zackie Oh!, the Hermosillo girls, and Chiara Paez—who was murdered and found buried in the backyard of the house of her boyfriend’s parents in Argentina—are all part of a cartography of power relations, of forces counting upon race, class, misogyny, and transphobia. These cases are not personal misfortunes, as is usually claimed by the mainstream news, but the result of misogynist biopolitics. This cartography does not connect all these bodies in a universalised neutral globalism; rather, it is drawn by points of reference, of situated localities, from which we can pin signs of our struggle on maps.

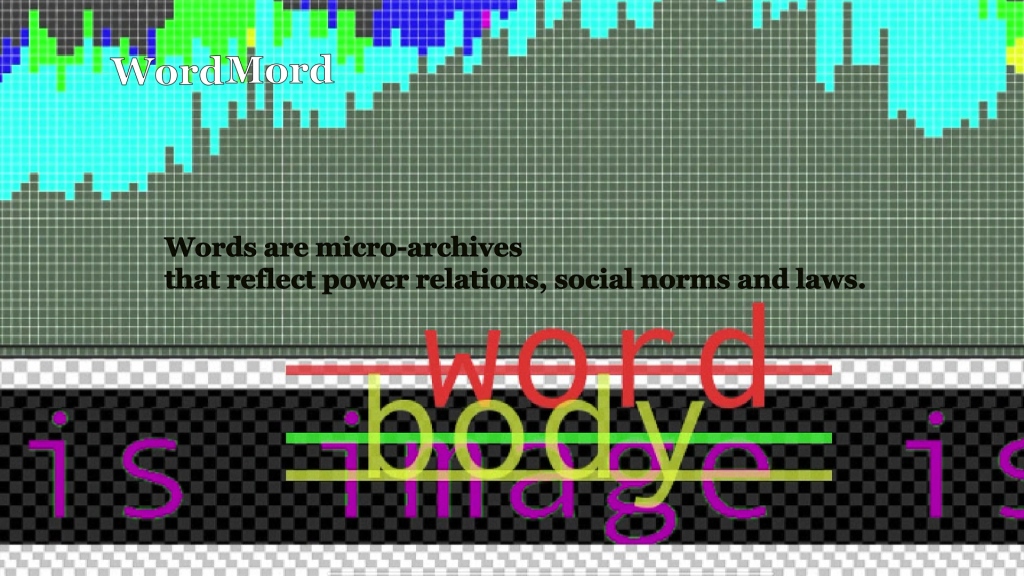

The ‘cartography of articulation’ is exercised, also, via another ‘aesthetic technique’. In the second phase of her* project, developed with the impetus of a memorial event for Zackie in Berlin in 2020, the artist created a video work as an open call for intra(action), addressed to activist groups and to the general public, to participate in a one-day laboratory.

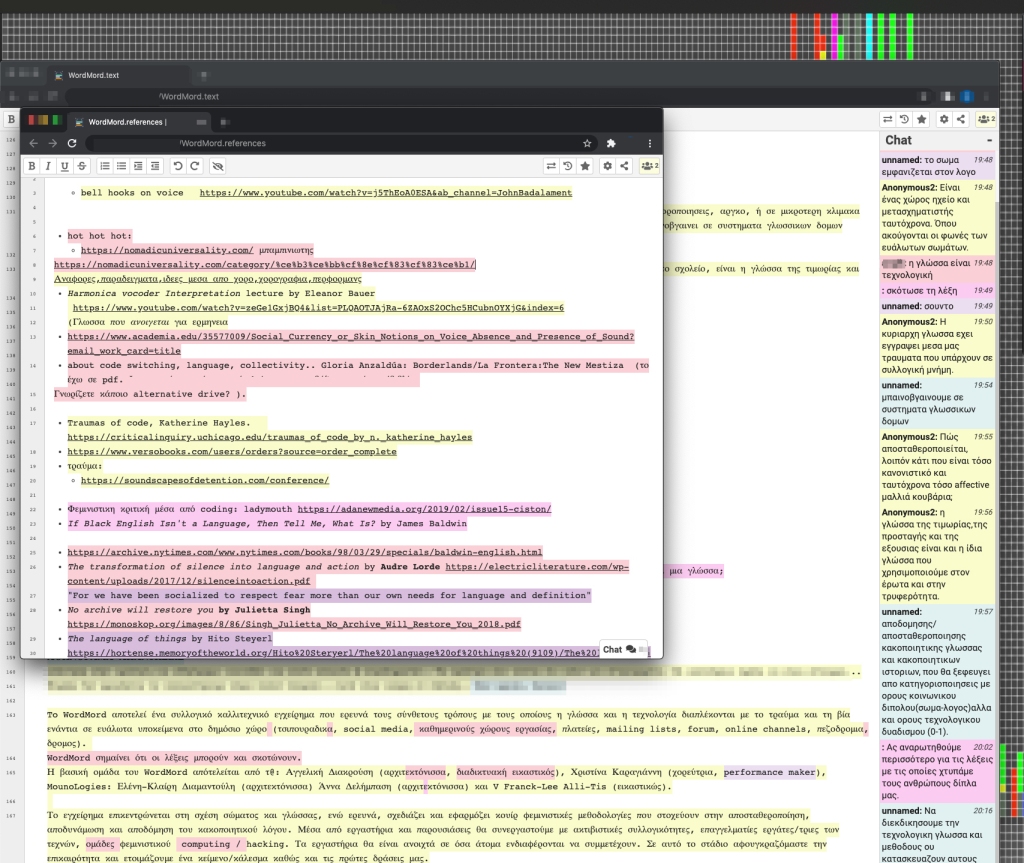

This led to the third phase of ‘WordMord’, in which the project became a collective project consisting of a research group including Vassiliea Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis, Angeliki Diakrousi, Christina Karagianni, Stylianos Benetos aka Oyto Arognos, and Mounologies: Eleni Diamantouli and Anna Delimpasi. In the third phase (2021-ongoing), the project evolves through workshops, presentations and (collective) artworks. Through collaborations with artists, activists and groups working on feminist coding, based on intersectional principles and questioning of the coding language, ‘WordMord’ seeks to design an online rhizomatic space as an active feminist archive. At the same time, the project provides tools and methods towards a poetically subversive meta/para/re-writing of derogatory narratives and, consequently, of trauma and violence. Archiving is an ‘instituting aesthetic technique’, a micro-geography that reveals the changes, the affiliations, the direction, that circulates, again; it is the presence of intentions and desires, a practice to make productive sense of the gaps and silences in history. An archive holds the “arche”, the commencement and the commandment, the beginning, the power and the authority, at the same time (as Derrida unravels in Archive Fever). Thus, within the archive stands the potentia carried by its content, as it becomes the very topos for certain matters to claim a presence. Here, the point is not to construct a homogenous, overarching, feminist practice but to activate the possibility of a diverse organisation.

In the 70s and the 80s, it became clear that there were conflicts, discomforts and vital antagonisms amongst feminisms, but it was also clear to some that coming together was politically essential and, in terms of action, stronger and more effective. It was also clear to some that this coming together was not to be based on grounds of generalised sisterhood or love but instead on grounds of ‘otherness’, of raising consciousness and underlining the different realities of class, colour, sexuality, ethnicity, and locality. In this sense, connecting the murder of Zackie Oh! to that of Topaloudi is not about merging them, for the specificities of these cases are different; it is about making apparent how female and trans bodies are targeted and considered extinguishable. Zackie Oh! and Topaloudi are ‘missing’ people. Whilst these cases can be seen in parallel, the archive does not tighten them together nor conflate them; on the contrary, they come together in the mind of the viewer, who draws connecting lines between the nodes. Looking for articulations of ‘missing people’ and convergences of different discourses and struggles might engender possibilities for fighting the unthinkable violence our humanist world is capable of. Cross-feminism articulations are imperative, but these articulations must be under constant negotiation, taking into account embodied and necessarily partial experiences and positions, as well as affective acts, friendships, and personal interactions. In this respect, there is considerable potential in interconnected and cross-feminist projects such as ‘WordMord’ that utilise different modalities (performance, video, archive, and workshop) as both integral parts of an art project and as alternative devices for the circulation of differentiated meaning, affect, and wording. Such projects can connect female and exploited bodies, as diverse as they may be, and encompass the possibilities of social change and drastic political pathways today. They open our political imaginaries to the possibilities of new attachments, affiliations and articulations that are not subsumed under abstract universal categories and values, nor limited only to identitarian affirmations of the political. It also impels us to look at and get inspired by movements and actions that occur in different times and places. Different cases of femicides initiated the protests Ni Una Menos in Argentina and #MiércolesNegro (the protest for Lucia Perez, a 16-year-old who was raped, tortured and killed). These are cartographies of resistance and polemical articulations. These protests could, imaginatively, poetically, and also actually, be connected to the murders of Zackie Oh! and Topaloudi. And, projects such as ‘WordMord’ can be used as nodes of our claims, political imaginaries, articulations, in addition to assisting us with the blind spots coming from our different positions, some of us white, heterosexual, western, some black, Asian, non-binary, queer etc with which (blind spots) many of us struggle and do not give up.

Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis’ practice consists of a paradigm of aesthetic techniques and a multimodal practice—spanning from lecture, video, archiving, workshops, as interchangeable formats—a paradigm of art in the expanded field. Krauss (1986) introduced the term ‘expanded field’ in her famous text ‘Sculpture in the Expanded Field’, proposing multiple extensions for sculpture, including sculptural forms, site constructions and axiomatic structures. In her text, she examines the ways post-war artists shattered and extended the boundaries of the traditional art medium by introducing spatiality and temporality, and the embodied experience, into artistic practice in radical new ways. Talking about methods and forms, Stylianidou aka Franck-Lee Alli-Tis’ practice expands into the interdisciplinary, intersecting with the tools of multimodal anthropology, as s*he turns her* attention to disentangle the experience and phenomena of the societal groups s*he focuses on: their attitudes, the rituals they perform in the street, in the media, on the internet, and in the language they use. The artist addresses the role that media (technologies), social media and devices play in our lives, the role they have in (re)presenting Zak, Maria, Dolores in certain ways, in (dys)selecting certain lives as worthy or unworthy. The work invites us to a conscious, active use of the modalities, devices s*he/we use, as we can either passively reproduce their violence or look for ways to resist it. Thus, in the case of ‘WordMord’, the defined aesthetic techniques in the expanded field—which find their genealogy in the above multimodal crossroads—traverse the physical, the virtual, the technological, the digital and the post-digital condition. It is about an expanded field that ranges from subjects to objects, to bots, to codes, from tangible to networked, from physical to virtual, and from real to imaginary. This video-lecture performance and the archive are embedded and embodied, and this constitutes the expanded field of a feminist technological art. These are aesthetic techniques that bring forth new contents and instruments for reformulating not only aesthetic production but the public domain itself. As the public domain is constructed by the way we perform ourselves, from the language we use and the position we take—in the streets, on social media, in any public expression towards critical issues—and by the institutions we form. Furthermore, the public domain is mutated while the feminist intellect becomes responsible for the representation, articulation, enunciation and instituting of meaning. These aesthetic techniques and artistic practices are, as theorist Jusi Parrika would say, not merely a description of the current state of how things are done but an identification of potentials of novel forms of emergent knowing, sensing and feeling. And these, as abstract or tangible they might be, ‘connote a completely material situation, locality and force’ (2019, pp. 44-45).

Notes

[1] “One way to live and die well as mortal critters in the Chthulucene is to join forces to reconstitute refuges, to make possible partial and robust biological-cultural-political-technological recuperation and recomposition, which must include mourning irreversible losses. Thom van Dooren and Vinciane Despret taught me that. There are so many losses already, and there will be many more. Renewed generative flourishing cannot grow from myths of immortality or failure to become-with the dead and the extinct”. Haraway, D,. 2015. Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene’. Environmental Humanities, vol. 6, pp. 161.

References

Braidotti, R., 2019. Posthuman Knowledge, Cambridge: Polity.

McKittrick, K., ed., 2015. Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis, Durham: Duke University Press.

Derrida, J., 1995. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Dolphijn, R. and Van der Tui, I., 2012. Interview with Rosi Braidotti. In: R. Dolphijn and I. Van der Tuin, ed. 2012. New Materialism: Interviews and Cartographies, Michigan: MP Publishing. pp. 19-37.

Haraway, D., 2015. Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin. Environmental Humanities, 6(1), pp. 159-165.

Krauss, R., 1986. Sculpture in the Expanded Field. In: R. Krauss, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. pp. 276-290.

Parikka, J., 2019. Cartographies of Environmental Arts. In: R. Braidotti and S. Bignall. ed. 2019. Posthuman Ecologies, New York, London: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 44-45.

Wiedlack, K., 2017. Gays vs Russia. Media representations, vulnerable bodies and the construction of (post)modern West. European Journal of English Studies, 21(3), pp. 241-257.

Elpida Karaba is an art theorist and independent curator. She is working at the crossroad of contemporary art, critical theory and emergent political manifestations in the public realm. She is a visiting lecturer at the School of Fine Arts, Athens. She is head of research at the Centre of New Media and Feminist Public Practices (www.centrefeministmedia.arch.uth.gr/), funded by the Hellenic Foundation for Research and Innovation (HFRI) and the General Secretariat for Research and Innovation (GSRI), based at the Department of Architecture, University of Thessaly. In 2014, she initiated the Temporary Academy of Arts (PAT)—a para-institution, an experiment of art, curating and pedagogy (www.temporaryacademy.org).